Memories form a core part of life, facilitating learning, maturation, and even survival. Now imagine not being able to form memories at all. Such was the case of Henry Gustav Molaison, a man who not only lost his memories, but his ability to form new ones.

Molaison was not always an amnesiac. At age ten, he started having seizures which escalated in severity as he got older (Lichterman, 2009). The seizures were so hindering that Molaison underwent temporal lobe resection at the hands of the neurosurgeon William Beecher Scoville (Dossani, Missios, and Nanda, 2015). This surgery involves the removal of mesial temporal structures such as the hippocampus and amygdala (Figure 1) (Al-Otaibi et al., 2012). However, the highly experimental surgery Molaison received had unforeseen consequences despite the reduced frequency of seizures. He developed retrograde and anterograde amnesia, a condition where he could not recall previous memories or form new ones respectively (Lichterman, 2009).

Molaison’s memory was not completely gone, for he retained general knowledge about the world along with language skills (Dossani, Missios, and Nanda, 2015). This led to follow-up studies done by Scoville and Brenda Miller, a graduate student from McGill University, where they examined ten patients who had undergone varying degrees of temporal lobe resection. This allowed them to definitively conclude that the removal of parts of the temporal lobe resulted in anterograde memory loss (Dossani, Missios, and Nanda, 2015).

Figure 1: A diagram of what Molaison’s brain would have looked like after the surgery in comparison to a regular brain. The missing part is where the hippocampus would have been, had it not been removed. H.M. stands for Henry Molaison, and he was often referred to by these initials to protect his privacy while he was still alive (Halber, 2018).

In more recent years, scientists have gotten a better image of how the brain forms memories. When an organism experiences an event, the cortical system is able to create a representation of entities involved in a generalized fashion. In other words, notably different objects can be distinguished, but similar ones are lumped together (Nadel et al., 2012). For example, the difference between apples and oranges can be distinguished, but two different apples cannot. Then, a second representation is formed where the contextual and spatial attributes of the event are formed. This hippocampal system also allows there to be distinctions between similar entities, your apple versus my apple. Finally, linkages form between the cortical and hippocampal systems leading to the formation of semantic memories (Nadel et al., 2012).

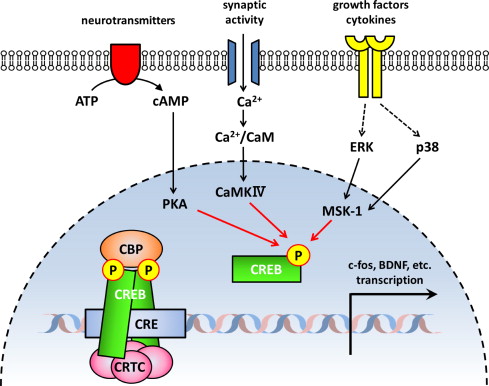

On a chemical level, memory is a dynamic process supported by many genes and transcription factors. A study by Mizuno and Giese in 2005, found that long-term memory requires gene transcription and de novo protein synthesis which is controlled by the transcription factor CREB (cAMP-response element binding) (Figure 2). CREB is involved in memory consolidation, a process that turns short-term memories into long-term ones (Mizuno and Giese, 2005). New gene expression mediated by CREB is required for this transition, which leads to plasticity changes in neurons (Kida and Serita, 2014). Since these changes occur in hippocampal CA1 (cornu ammonis 1) neurons, Molaison was not able to form new memories as his hippocampus was removed. Another study by Levenson et al. 2004, found that hippocampal histone acetylation is tied to memory formation. They found that contextual fear conditioning of rats increased the acetylation of histone H3 in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. acetylation causes a change in the chromatin structure allowing the transcription of proteins which leads to the activation of the ERK (Extracellular signal-regulated kinase) signaling cascade. The ERK protein is critical in establishing long and short-term memory as it has several functions including regulation transcription factors such as CREB (Levenson et al., 2004).

Figure 2: The CREB pathway which is involved in memory formation and enhancement. It is downstream of the cAMP (red protein), Ca2+ (blue protein), and ERK (yellow protein) signal transduction pathways. The products of these pathways, protein kinase A (PKA), calmodulin-dependent kinase IV (CaMkIV), and Mitogen and stress-activated kinase (MSK-1) phosphorylate CREB. When CREB is phosphorylated, it binds to cAMP-response element (CRE), which is part of the protein complex involving CREB-binding protein (CBP) and CREB-regulated transcription coactivator (CRTC). Together these components initiate the transcription of genes necessary for memory formation (Kida and Serita, 2014).

The legacy and impact that Henry Molaison had on the field of neuroscience was profound. His case led to several discoveries, including the duration of short-term memory. Molaison could remember things within 30 seconds of them happening, but struggled beyond 60, demonstrating that short-term memory lasts less than 60 seconds (Shah, Raman Deep, and Sagar, 2014). He also led to the distinction between semantic and episodic memory, with him losing the latter. This is due to semantic memories being permanently solidified in the cortex, while episodic memory is stored in temporal lobe structures which Molaison had removed. Most importantly, it was shown that people can learn using only implicit memory. Molaison was able to learn new motor skills, such as using a walker, which demonstrated that some memories were not hippocampus-dependent (Shah, Raman Deep, and Sagar, 2014). Today, Molaison’s brain has been preserved for further study and was sliced and stained one year after his death (Buchen, 2009). The 2400 brain slices allow neuroscientists to test hypotheses by examining the anatomy as well as the precise brain lesions Molaison received from the resection.

In conclusion, Henry Molaison played a vital part in our modern understanding of memory formation and its association with the hippocampus. He helped us learn where and how memories are formed and brought to light many unknown facets of how memories are stored. While Molaison could no longer form memories, he will always be remembered as a great contributor to neuroscience.

References

Al-Otaibi, F., Baeesa, S.S., Parrent, A.G., Girvin, J.P. and Steven, D., 2012. Surgical Techniques for the Treatment of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Epilepsy Research and Treatment, 2012, p.374848. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/374848.

Buchen, L., 2009. Famous brain set to go under the knife. Nature, 462(7272), pp.403–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/462403a.

Dossani, R.H., Missios, S. and Nanda, A., 2015. The Legacy of Henry Molaison (1926–2008) and the Impact of His Bilateral Mesial Temporal Lobe Surgery on the Study of Human Memory. World Neurosurgery, 84(4), pp.1127–1135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.04.031.

Halber, D., 2018. The Curious Case of Patient H.M. [online] BrainFacts.org. Available at: <https://www.brainfacts.org/in-the-lab/tools-and-techniques/2018/the-curious-case-of-patient-hm-082818> [Accessed 22 November 2022].

Kida, S. and Serita, T., 2014. Functional roles of CREB as a positive regulator in the formation and enhancement of memory. Brain Research Bulletin, 105, pp.17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.04.011.

Levenson, J.M., O’Riordan, K.J., Brown, K.D., Trinh, M.A., Molfese, D.L. and Sweatt, J.D., 2004. Regulation of Histone Acetylation during Memory Formation in the Hippocampus *. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279(39), pp.40545–40559. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M402229200.

Lichterman, B., 2009. Henry Molaison. BMJ, 338, p.b968. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b968.

Mizuno, K. and Giese, K.P., 2005. Hippocampus-Dependent Memory Formation: Do Memory Type-Specific Mechanisms Exist? Journal of Pharmacological Sciences, 98(3), pp.191–197. https://doi.org/10.1254/jphs.CRJ05005X.

Nadel, L., Hupbach, A., Gomez, R. and Newman-Smith, K., 2012. Memory formation, consolidation and transformation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(7), pp.1640–1645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.001.

Shah, B., Raman Deep, P. and Sagar, R., 2014. The study of patient henry Molaison and what it taught us over past 50 years: Contributions to neuroscience. Journal of Mental Health and Human Behaviour,India, 19(2), pp.91–93. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-8990.153719.