Imagine standing at a busy intersection in downtown Hamilton. You can hear tires screeching, and the smell of exhaust fills your nose. In fact, it fills a lot more than your nose: it fills your lungs, possibly causing severe respiratory conditions like asthma (Gillissen and Paparoupa 2015).

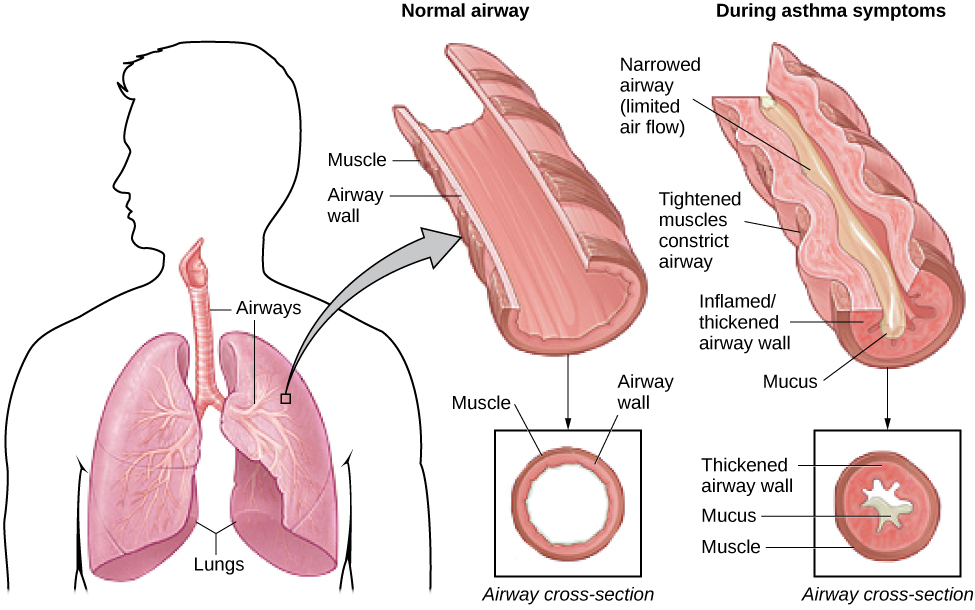

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease that can be triggered by the deposition of harmless or harmful environmental compounds in the airway (Gillissen and Paparoupa 2015). Within the respiratory tract, the body can overreact to these unknown substances, such as pollen or pollutants, causing an asthmatic reaction. This is characterized by wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness (Tiotiu et al. 2020). In those with asthma, the layer of smooth muscles in the bronchi contract in a process called bronchoconstriction to respond to particulates (Figure 1) (Sinyor and Concepcion Perez 2023). Over several hours, white blood cells cause further bronchoconstriction and trigger inflammation. In some cases, mucous production is also upregulated, causing a buildup and blockage in the airway (Gillissen and Paparoupa 2015).

Figure 1: The respiratory system is shown on the left. The airway consists of the trachea, which splits into the bronchi, extending into the left and right lungs (Sinyor and Concepcion Perez 2023). The bronchi branch into secondary and tertiary structures and eventually branch into bronchioles. In a normal airway, the muscle lining the bronchi is relaxed, with no inflammation. The airway is clear of particles and mucous, with a large radius. In the case of asthma, the muscles are constricted and become inflamed, narrowing the airway and limiting airflow. Hypersecretion of mucous further blocks the airway. [Image from (Spielman et al. 2024)].

Poiseuille’s Law can be used to understand airflow loss in asthma (Equation 1). Since radius is to the power of four, a small decrease in airway radius drastically decreases airflow. To compensate for the decreased airflow, the body tries to increase pressure. When the diaphragm relaxes to decrease the volume of the lungs, pressure is consequently increased (Campbell and Sapra 2025). Due to the radius having a much larger effect than the pressure, outgoing airflow is still reduced overall, causing air to be trapped in the lungs, leading to asthma attacks.

Q = πPr4/8ηl

Equation 1: Q = flow rate, P = pressure, r = radius, η = viscosity, and l = length.

Air pollution is categorized into gaseous and particulate matter (PM) (Tiotiu et al. 2020). Particulate matter is further divided into PM2.5, which has a diameter less than or equal to 2.5 μm, and PM10-2.5, which has a diameter between 10 and 2.5 μm (Keet, Keller, and Peng 2018). This is about 1/70th the diameter of a human hair. PM2.5 is formed from combustion or atmospheric reactions, whereas PM10-2.5 is derived from the grinding and resuspension of solids, such as tire wear. Traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) is a subset of PM10-2.5, which is now recognized as the more harmful of the two particulates (Tiotiu et al. 2020). Although PM10-2.5 does not penetrate as deep into the lungs, it deposits in the upper airways, causing obstructive lung diseases (Keet, Keller, and Peng 2018).

Air pollution is variable, being influenced by factors such as meteorological events and human activity (Tiotiu et al. 2020). Daily variation in TRAP causes differences in the short-term effects of asthma, such as increased asthma hospitalizations and emergency department visits when TRAP levels increase (Keet, Keller, and Peng 2018). Additionally, the effects of TRAP on asthma are predominantly seen in children, which is likely because asthma typically develops at a young age. It is also suspected that children are more susceptible since they tend to spend more time outside and their immune systems are still developing.

The effects of air pollutants extend much further than the environment: they are a direct detriment to human health. As urbanization drives TRAP higher and action continues to not be taken, future generations will be left wheezing and gasping for solutions.

References

Campbell, Miles, and Amit Sapra. 2025. “Physiology, Airflow Resistance.” In StatPearls. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554401/.

Gillissen, Adrian, and Maria Paparoupa. 2015. “Inflammation and Infections in Asthma.” The Clinical Respiratory Journal 9 (3): 257–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.12135.

Keet, Corinne A., Joshua P. Keller, and Roger D. Peng. 2018. “Long-Term Coarse Particulate Matter Exposure Is Associated with Asthma among Children in Medicaid.” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 197 (6): 737–46. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201706-1267OC.

Sinyor, Benjamin, and Livasky Concepcion Perez. 2023. “Pathophysiology Of Asthma.” In StatPearls. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551579/.

Spielman, Rose M., William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett, et al. 2024. “12.3: Stress and Illness.” In Introduction to Psychology-PSYC201. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/City_Colleges_of_Chicago/Introduction_to_Psychology-PSYC201/12%3A_Stress_Lifestyle_and_Health/12.03%3A_Stress_and_Illness.

Tiotiu, Angelica I., Plamena Novakova, Denislava Nedeva, et al. 2020. “Impact of Air Pollution on Asthma Outcomes.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (17): 6212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176212.