American football is one of the most popular yet violent sports in the world; each season, players accrue injuries ranging from common sprains to career-threatening spinal fractures (Saal, 1991). In the United States, football continues to account for the highest proportion of concussions, a trauma now emerging as a significant health risk to long-term cognition, emotion, and behaviour (Clay, Glover and Lowe, 2013). Understanding the causes of concussion incidence and its consequences are vital to optimising player safety and enhancing future protocols.

A concussion is traditionally believed to involve a primary and secondary injury phase. The primary injury is characterised by the moment of impact between players where kinetic energy and force vectors are transferred in either a linear acceleration-deceleration mechanism, rotational mechanism, or combination of both (Dashnaw, Petraglia and Bailes, 2012). To visualise the primary stage more clearly, imagine a “clothesline”: an unanticipated, head-on collision between a ball carrier and a defender that results in a whiplash-type force on the offensive player (Barth, et al., 2001).

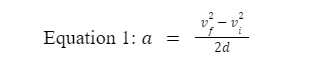

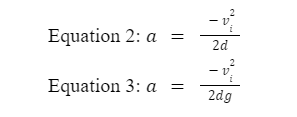

By applying fundamental kinematics (Equation 1) to this situation, we can calculate the stresses placed on neural fibres and determine the potential for neurocognitive impairment on the ball carrier (Barth, et al., 2001). Here, a is the acceleration, vf is the final velocity, vi is the initial velocity, and d is the distance travelled during deceleration.

In this specific circumstance, the ball carrier comes to rest at the end of the impact (vf = 0), reducing Equation 1 into Equation 2. Dividing Equation 2 by acceleration due to gravity, g, produces Equation 3, acceleration as a multiple of g (Varney and Roberts, 1999).

Using game film, we can estimate the offensive player’s initial velocity to be 8.13 m/s and the stopping distance of his head to be 0.152 m. Substituting 9.8 m/s2 and solving produces a result of 22 g. Acceleration of 30 g or greater is generally cited as the mark for irreparable brain injury in severe vehicle crashes (Barth, et al., 2001). By virtue of Newton’s Second Law of Motion, we now know the force on a 1 lb section of the player’s brain—such as his anterior frontal lobe—experiences a 22 lbs force during this hypothesised collision (Varney and Roberts, 1999).

This unbalanced force on the player’s head causes the brain to accelerate and strike the inner skull in the direction he was travelling. The brain will then rebound from that collision and strike the skull lining on the opposite side, inducing axon deformation and tear, seen in Figure 1. In a clothesline, the offensive player may even experience twisting or rotational forces due to whiplash, potentially causing greater impairments to neurobehavioral outcomes (Barth, et al., 2001).

Figure 1: Pictorial representation of a concussion in football. The bottom-half of this image depicts a head-on collision between two players causing direct impact on the skull. As the skull deforms, the brain accelerates and hits the back of the skull. This rapid impact causes the soft tissue of the brain to strain, stretch, and tear blood vessels. If delicate nerve fibres are damaged, the brain’s functioning can be degraded. The top-half of this image depicts an even riskier situation in which a player can crash into a stationary object such as a goalpost. This can considerably decrease the stopping distance, d, in Equation 3, creating an even larger resulting force on the brain. The possibility of sustaining a severe injury in this case is higher (Musumeci, et al., 2019).

The secondary injury phase refers to the physiological changes to neuronal functionality after a concussion. When neuronal membranes are strained, dysfunctional ion flow begins; calcium and sodium enter the neuron while potassium flows out. Following neuron firing, excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate are released, furthering the state of neuronal ionic imbalance, seen in Figure 2. Sodium-potassium pumps desperately attempt to restore homeostasis, but due to these pumps requiring ATP, energy is quickly exhausted (Howell and Southard, 2021). As a result, players often experience fatigue, slowed processing, and impaired cognition after a concussion-related injury (Giza and Hovda, 2014).

Figure 2: The biological processes that occur in a neuron after a concussion. After the brain rapidly strikes the skull, axons are damaged (axonal injury). In response to new stimuli, the brain is activated and ionic flux occurs. Calcium and sodium ions enter the neuron (depolarization) and potassium ions exit the neuron (repolarization). The excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate is released, triggering ligand-gated ion channels in surrounding neurons to also increase ionic flow rate. This causes widespread inhibition of neuronal activity which manifests itself as slower processing symptoms. ATP-requiring sodium-potassium pumps frantically attempt to restore homeostasis but quickly deplete energy stores. As calcium ions flood the inside of the neuron, oxidative phosphorylation is disrupted, which damages the mitochondria and its ability to produce energy (cell death) (Giza and Hovda, 2014).

Despite these understandings, football remains a high-risk sport. Concussions will continue to pose a unique challenge for players, coaches, and physicians alike. To ensure the well-being of current and future players, team personnel must foster a culture that prioritises player safety above all.

References:

Barth, J.T., Freeman, J.R., Broshek, D.K. and Varney, R.N., 2001. Acceleration-Deceleration Sport-Related Concussion: The Gravity of It All. Journal of Athletic Training, 36(3), pp.253-256.

Clay, M.B., Glover, K.L. and Lowe, D.T., 2013. Epidemiology of concussion in sport: a literature review. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 12(4), pp.230-251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2012.11.005.

Dashnaw, M.L., Petraglia, A.L. and Bailes, J.E., 2012. An overview of the basic science of concussion and subconcussion: where we are and where we are going. Neurosurgical Focus, 33(6), pp.1-9. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.10.FOCUS12284.

Giza, C.C. and Hovda, D.A., 2014. The New Neurometabolic Cascade of Concussion. Neurosurgery, 75(4), pp.24–33. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000000505.

Howell, D.R. and Southard, J., 2021. The Molecular Pathophysiology of Concussion. Clinics in sports medicine, 40(1), pp.36-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2020.08.001.

Musumeci, G., Ravalli, S., Amorini, A.M. and Lazzarino, G., 2019. Concussion in Sports. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 4(2), pp.1-8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4020037.

Saal, J.A., 1991. Common American Football Injuries. Sports Medicine, 12(2), pp.132–147. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199112020-00005.Varney, N.R. and Roberts, R.J., 1999. The evaluation and treatment of mild traumatic brain injury. 1st ed. London: Psychology Press.

Comments

5 Responses to “The Unsettling Concussion Crisis in American Football”

Hi iSci!

Earlier this NFL season, Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa suffered a severe head and neck injury while attempting to escape a tackle from an opposing player. This incident compounded another concussion-related injury Tua faced four days earlier in which he demonstrated gross motor instability after completing a pass. Watching this game live was chilling; Tua’s fingers twitched in an unnerving manner and was stretchered off the field shortly after. This game sparked my interest in head trauma and what neuroscientific concepts explain concussions. This content is a direct application of kinematics from first year physics and neurobiology concepts from the 2A18 neuroscience RP.

If you have any comments for how I can improve this draft for its final submission, please list them below. Thank you so much for reading.

Have a great day!

Rith

Hi Rith!

This was a very interesting and well-written post… I had trouble finding many things to comment on! I do have a few very minor suggestions for you to consider:

P2 S2: This sentence is a bit long, and could be split into two sentences. I’d suggest splitting somewhere around: “… moment of impact between players. During this collision, kinetic energy and force vectors are transferred… “

Equations 2/3: It would be useful to the reader if you gave more context to these two equations, like you did with equation 1 (by explaining that this represents the stresses placed on neural fibres). Do equations 2 and 3 represent a particular effect on the ball carrier? Or are they representative of the stresses placed on neural fibres at different stages in the collision process? If this is the case, I’d recommend adding a sentence explaining this to the reader.

P5 S4: You mention that the anterior frontal lobe experiences a large amount of force in this sentence, but there is no reasoning for why this part of the brain was used as an example. Is the anterior frontal lobe important for any particular reason (is it especially susceptible to this force)? Is there a particular outcome that will occur due to a large amount of force being placed on this part of the brain that is different from other parts of the brain?

Figures 1/2: I just wanted to mention how great your figures are! They do an awesome job of illustrating the concepts you discuss in your post.

P8: If you have the word count, it would be great to tie the conclusion in with your introduction. In the intro, you mention that understanding the cause of concussions can enhance future treatment. An additional sentence or two explaining how specifically our understanding of concussions helps in the treatment development process would round out your post nicely. Are there any specific treatments under development currently?

Overall, you did an amazing job with this post, and I’m looking forward to reading the final draft! Best of luck in the editing process.

Cheers,

Ava

Hi Ava, thank you very much for your comments. Here are my responses:

1. I agree, and I have changed this sentence by simplifying a bit.

2. This was a great point, and I have included this in my final draft.

3. You are exactly right! The anterior frontal lobe is highly susceptible to damage during a concussion because it is the foremost part of our brain. This is represented in Figure 1, but the more important message to take away from this part is that the force on any 1 lb section of the brain is multipled 22 times by this hypothetical collision.

4. Thank you very much!

5. I did not have the word count for this, but I have edited my introduction to be more aligned with the conclusion.

Thank you for all of your comments, they were all extremely helpful!

Rith

Hi Rith,

This is a really cool blog post! Your topic is very interesting to me since I played contact sports throughout my childhood and I have (unfortunately) become very familiar with concussions. I think you did a great job touching on the relevance of this topic and explaining the biophysics involved! Here are a few things that I noticed while reading:

• While the second sentence of your first paragraph is very relevant and informative, it is quite complicated and might be a little difficult to follow. Consider breaking it up slightly or omitting some of the more technical terms.

• In the first sentence of your third paragraph, your reference to Equation 1 is somewhat inconsistent. To remedy this, you could say “By applying a fundamental kinematics equation (Equation 1)” or simply “By applying fundamental kinematics (Equation 1)”. I’m also unsure of your use of “condition” in this sentence because I think you’re referring to the scenario you’ve just described, but I feel that “condition” could imply specific reference to the concussions as a medical condition in general. Either way, replacing it with “scenario” or “situation” might be better.

• You do a great job of using figures to supplement the processes that you explain in-text! I like that you included plenty of detail in the captions, but keep in mind that you don’t want figures and descriptions to be so big that they dominate the page and take away from the text itself.

Overall, this is a really interesting blog post and I thoroughly enjoyed reading it! It is very well written and I learned lots of new things about the physics and neurophysiology associated with concussions that I wish I’d known sooner! I hope you find my suggestions helpful, and happy editing!

Cheers,

Andrew

Hi Andrew, thank you so much for taking the time to read my post and suggest some comments. Here are my responses:

1. I can see this, and I have edited my final draft to fix this sentence.

2. Thank you for these suggestions! I have implemented them into my final draft.

3. I completely understand this, and have made my captions as concise as possible.

Thank you for your comments, they were all so helpful.

Rith